Late in his ninth decade and conscious the sands of his time may be too diminished to finish all he should, Jim Bowler speaks at night to the ancient Aboriginal person who has defined his life, Mungo Man.

Geologist Bowler – snowy-haired, clear-eyed and fit at 87 – discovered the remains of the modern Indigenous Australian man, at least 40,000 years old, in the Willandra Lakes region of New South Wales in 1974, having previously found those of a perhaps equally ancient female in 1968.

Bowler has since wrestled with the implications – for cosmology and philosophy, for science and religion, for Australian race relations and humanity. His Mungo Man-inspired thoughts range across the genesis of earthly life, Celtic mysticism and the clashes between rationality and intuition, science and the Dreaming, the sacred and the profane. He is lucid and compelling.

The discovery of the ancient skeletons has captivated a legion of scientists and philosophers for 50-plus years, and this week Mungo Man’s remains begin the journey from the National Museum of Australia in Canberra back to country.

Bowler – the last surviving member of the discovery party – is urgently trying to finish a book on the subject but, he points out, speaking and thinking about it is different from writing it down in a linear narrative. He’s stuck, and he admits he may never finish.

And so he speaks in the dark hours to Mungo Man, a photograph of whose remains is on the wall of the small bedroom-study-archive of his home in bayside Melbourne.

“I say to him, ‘What is your message?’ And I anticipate his message is, ‘What have you done to my land? What have you done to my people?’ If he was alive, that’s what he’d say. Out of death there is a creation of new energy and there’s opportunity here to acknowledge the [Aboriginal] dead, the elders – and the 20 or 30,000 people who’ve died in defence of their country [in black-white frontier conflict].”

Given his subsequent objectification as the oldest Indigenous human remains on the Australian continent, Mungo Man might well curse the scientists who removed him and kept him away from country for the past four decades. But he might also take satisfaction that his discovery proved what the local Indigenous peoples – the Paakantji, Mutthi Mutthi and Ngiyampaa – have long known: their people have effectively been there forever.

For Bowler, his discovery of Mungo Man was the ultimate clash of modernity and intuition; a moment that crystallises everything unresolved in black-white Australia.

“We are dealing with the conflict of white rational, sophisticated science enlightened by the bloody Enlightenment, translated into an Aboriginal land ... with an Aboriginal people with an entirely intuitive and empathetic relationship with country,” he says.

“That Enlightenment was superimposed both on a country they [the ‘enlightened’] didn’t understand and a people they didn’t understand ... and we now carry the burden of the fucking Enlightenment. This is because the purely rational mind is incapable of understanding what Aboriginal people are fundamentally on about.”

As Mungo Man’s long overdue repatriation arrives, Bowler muses on his life and its intersection with the bones he found in the dry lake bed in 1968 and 1974.

Images of two others, besides Mungo Man, adorn the walls of Bowler’s room, whose shelves, desk – even bed – are crammed with papers, files, various publications and notebooks. One is a photograph of his father James, an Irish fisherman who migrated in the early 20th century to farm near Leongatha, southern Victoria. The other is Christ, as depicted in a Tibetan monk’s Thangka.

“They are the three men in my life,” Bowler says.

‘Here is the evidence, take it or leave it’

James Bowler, the fisherman from the Blasket Islands, was the only survivor when the mackerel boat he was working in sunk after striking the sandbar at Smerwick harbour. A Catholic with a healthy disregard for clericalism, he migrated to Gippsland where he dug the rich dirt as an onion farmer and married, before digging in amid the mud and the blood and the horror of the Somme for two years during the first world war. He came back to the land. He kept men in work, local families in food, during the Great Depression.

Jim junior grew up grubbing in the soil too, helping with the back-breaking business of onion growing. Educated by the Marist Brothers, after school he saw four life options: farming, law, medicine or the priesthood. He chose the last, training to be a missionary priest at the Jesuit Corpus Christi seminary in Werribee, Victoria.

He loved the English literature class of Father Barney O’Brien; Yeats, Keats, Shelley and Shakespeare captured his imagination, rolled off his tongue. But he could forego the rest.

“I looked outside and there was a whole world going on out there. There was all these beautiful women and sexuality, and fun and games,” he says.

He lasted nine months in the seminary before retreating to the family farm where his father gave him a few acres on which to raise his own onions. Bowler instead planted potatoes (less back-breaking, he reckons). Digging spuds, he quoted Hamlet. The symbolism, even prescience, of this is irresistible and profound, given the existential implications of the Aboriginal craniums – especially that of Mungo Man – he’d find in that dry lake bed a couple of decades later.

He farmed potatoes for 10 years or so, studying philosophy by correspondence and acquiring campfire wisdom from an eclectic bunch of alcoholic itinerant workers – men who’d run away to sea or war as teenagers, jailbirds and military deserters. They’d dig three days a week and blow their wages on drink by Friday night, wake up in the local cells come Saturday.

In his late 20s Bowler began studying earth sciences at the University of Melbourne.

“I’d had my nose in the soil for 25 years so I latched on to geology. It made sense. As part of that I became fascinated in the fact that here we’re in Australia and we’ve got all these deserts ... but they’re not really deserts, they’re big lakes with no water. And so climate change became my area.”

He went back and forth to the farm. While visiting he arranged a meeting with a prominent Gippsland local, Murray Black. Black was a mining engineer descended from the earliest “settler” families of the district.

Black has long intrigued – and repelled – me. I’ve written extensively about how he compulsively, in the name of natural science, sought out and systematically ransacked Aboriginal burial grounds across Victoria and New South Wales to supply Indigenous bones (especially skulls) to research institutions including Melbourne University and Canberra’s Australian Institute of Anatomy.

Since Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution and the work subsequently carried on in his name by Thomas Huxley (“Darwin’s bulldog”) and a legion of other disciples, institutions the world over had clamoured for Aboriginal skulls in the fallacious belief they represented a step in the evolutionary chain between ape and man. Cranial profiling (including, until the 1940s, the voodoo science of phrenology) was critical to the racial stereotyping of Indigenous Australians as primitive rather than modern people.

Black collected thousands of skulls and complete skeletons for no gain beyond the acknowledgement afforded him by the institutions he supplied and, apparently, a macabre compulsion conducted in the name of science.

When Bowler interviewed Black, he was given documents and detailed maps of sacred burial grounds that he had plundered. He shows them to me, says “I came to the university and discovered what Murray Black had been doing. I came home on a weekend and … I had a motorbike and a little tape recorder so I went down and interviewed Murray Black. I taped his story … and then of course I lost the tapes … that’s the story of my chaotic archive.”

“That whole process that he was involved in ... comparing Neanderthals that had already been found in Europe with Aboriginal skulls. There was already a huge collection of skulls in England. Then the physical anatomists just followed that up and it became almost an unholy competition. Cranial profiling,” Bowler says.

“He [Black] told me a story about how he’d been collecting up around the Murrumbidgee over a summer period and he had two truckloads of skeletons ... By the time they got back, the silverfish had eaten the labels ... they were useless. So they were all dispatched to the institute of anatomy, where they stayed until about 25 years ago.”In the late-1960s Bowler was researching the composition of the lakes for the Australian National University. He would scour the lake beds by motorbike, camping remotely away from home, often by himself.

He was already finding evidence in shell middens that pointed to ancient human existence.

“When I was first out at Mungo and told my colleagues about midden shells on top of the dunes they said, ‘Oh, bloody birds put them there’. But I knew that at least the top five metres had gone so that these were at least 25,000 years old. And they said ‘No, no, no, Bowler - the oldest evidence of humans then was in Kakadu – 20,000. No, there’s nothing out there beyond 20,000, stick to your stones’,” he recalls.

“So I’m sticking to my stones. But in the back of my mind I’m thinking ‘I’m going to teach these buggers right’. I knew what I was on about and that they were wrong. The irony of it is that I was walking back [to the camp] in the very early days out there and here are these burnt bones coming out of a big block of soil ... bones ... and here is a burning site ... they were femurs and so forth. And I thought, ‘This is something I’m not going to touch’. So I put a peg in. I went back ... and presented a paper at a seminar saying ‘Here is the evidence, take it or leave it’, and immediately afterwards I was invaded by the archaeologists saying ‘we’ve got to get out there’.

A few months later a party including the ANU’s John Mulvaney – a friend and mentor to Bowler known as the “father of Australian archaeology” – drove out to Mungo.

Bowler pointed the archaeologists to the body that would become known as Mungo Lady, while he took others to see the middens he had previously found.

“The archaeologists are ordained – you know, they are like priests, only they can handle the sensitive objects. It was a moment – bang! That was a moment when things jumped – the moment when the story of the occupation of Australia suddenly changed. I took my other colleagues up to see the evidence of the midden shells. When we came back all the items [the body] had gone – been swept into John Mulvaney’s suitcase,” he says.

The physical anthropologist Alan Thorne took months to re-piece the skeleton, especially the cranium.

“And at this stage we knew the date was at least 24,000 or 25,000 and we knew we had modern people. [Remains taken from] Kow Swamp [were] ... thought to be more archaic and ancient in morphology but were only 12 to 19,000 years old. The modern cranium [of Mungo Lady] was considerably older, which was the wrong way around for the cranial profiling fellows.

“I think we can say ... that was the end of cranial profiling ... that business of Darwin and Huxley and Murray Black and all those bloody others had been involved in.”

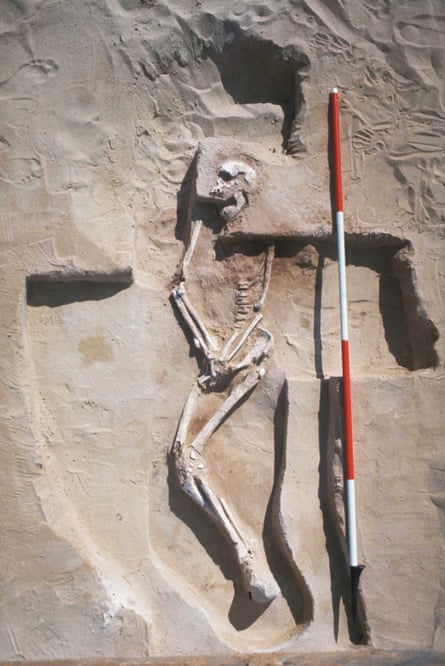

Six years later, in February 1974, Bowler found the body of Mungo Man while digging in the lakes with Mulvaney.

Fire had yet again been central to the funeral ceremony, as was a type of ochre brought to the site from 200kms away. The body was laid out, with the ochre and the fire, legs slightly bent and hands joined over the pelvis, part of a sophisticated ritual.

Bowler says, “The anointing of the body in that nature is the sort of ritual that would be acceptable in any cathedral today. And there you’ve got the fire – think the smoke and the incense ... so to have that in our backyard 40,000 years ago, there’s nowhere else in the world that happens ... think of it in the context of cultural continuity of the present Aboriginal people. Not even ... the Indigenous people of Africa ... have that connection to anything like that continuity of culture. So we are sitting on an extraordinarily privileged place in humanity.

“The story of humanity is in the story of those Mungo people. We are cosmophiles – we are cosmopholic. We are connected to the cosmos. This is what you find in that situation – that ritual, these were people of the sun and the stars and the very landscape they lived in.”

‘There’s old Mungo Man – and he’s 36,000 years before Abraham”

Bowler and I have been communicating for a few years now. He sought me out after I began writing about the theft of Indigenous remains by the likes of Murray Black, cranial profiling and what I believe should be the national imperative of repatriating from overseas and returning to country the Indigenous remains stolen for institutions the world over. It’s the first time we have met.

We talk about his six children and the cost to them – and his wife – of having a father and husband who was so frequently absent. Even now, he says, as he struggles to write about the meaning of Mungo Man, he still can’t dedicate the time to family he feels he should.

“All of Joan’s friends are going overseas and travelling and I just have to say, ‘I can’t do that because if I fall off my perch tomorrow I’ll leave a trail of unfinished business’.”

For Bowler, the book must make sense of why Mungo Man is central to the cosmos.

It goes something like this: Indigenous belief in an animated Earth and solar system, whereby totemic animals and other beings made everything – and in so doing became part of its story – are inextricably linked to the ancients of this continent. Mungo Man and Lady are central to that human beginning. They and their contemporaries are in the songlines that criss-cross the lakes. In Indigenous cosmology, they are the closest humans to Australia’s – and the world’s – beginnings.

Yes, it’s mind-bending. But no more so than any wrestle with theology.

Bowler’s brand of Catholic belief has roots in Celtic mysticism, which was itself replete with an animated Earth.

Bowler says, “If you try telling the Jews and the Arabs to love each other today you’ll get strung up. That’s what happened. Christ was a troublemaker. Where I come from does influence what I believe – and I’ve rejected a lot of the dogmatic bullshit that we were taught at school. But early Celtic tradition was very different from the Roman Catholic church. Early Celtic tradition is a monastic tradition I relate to. In those days the land was animated – there were elves and fairies and the dreaded Banshee.”

We discuss the perfection of an Indigenous belief system that can incorporate creationist animals and the country they made, the elements and the solar system, Christianity and Islam, and continuity between the Earth, human origin and faith.

Bowler says, “There’s old Mungo Man – and he’s 36,000 years before Abraham.”

If Abraham is a prophet to Christians, Jews and Muslims, Mungo Man and Lady are certainly no less to Indigenous – and perhaps many other – Australians and Indigenes the world over.

“Life comes from bloody rocks. Now we can trace the story of life back to the stromatolites out on the Pilbara ... the first organic life as microbiology with sun and photosynthesis comes the first evidence of life. You wind that up, you come through the vertebrates, the hominids and you come to art and language and us. We come from the bloody cosmos and through us now the cosmos is exploring itself. Which is a bit of an oxymoron.”

“You see, when I start talking to my scientific colleagues, if I start talking about spirituality and Indigenous wisdom and belief they say, ‘well poor old Bowler, he’s gone all religious or something’. But that’s the language we have to discover.”

‘There had to be a keeping place. There isn’t, and that is wrong’

While no single tribal group was evident at the lake when either Mungo Man or Lady were taken, there was an outcry from Indigenous people at the removal of the second body. It was a new era of Indigenous activism; of protest (not least with the establishment of the Canberra Aboriginal embassy); of pre-native title land claims and grants.

Aboriginal people associated with the lakes district were angry they had not been consulted but agreed to work through a formal “consultation” process while research had been carried out on the remains. Some wanted the remains returned and reburied immediately.

Bowler, Mulvaney (who died in 2016) and others had always intended the body of Mungo Man to be swiftly repatriated to an appropriate keeping place. Mungo Lady was returned to country in 1992 where she is held in a secure facility associated with the Mungo national park. Mungo Man will be similarly stored, having been kept at the ANU until 2015 and more recently in the National Museum of Australia’s human remains storage facility on Canberra’s outskirts.

Bowler and his family will take part in the elaborate repatriation ceremony. They have donated 8,000-year-old redgum wood for his coffin, which will travel in a cortege back to country. The remains of another 100 or so associated with the district will also be repatriated. But Bowler is displeased that federal and state governments have not supported, in practical terms, an appropriate keeping place.

“My concern is that there will be a big celebration when Mungo Man goes home. It will be on the TV and radio news. And then he will go into a basement and be forgotten. There will be no appropriate keeping place, which is what Mulvaney and I always wanted – the Aboriginal people could say where it went. But there had to be a keeping place. There isn’t, and that is wrong,” Bowler says.

A keeping place befitting a man who might just be Australia’s own prophet.