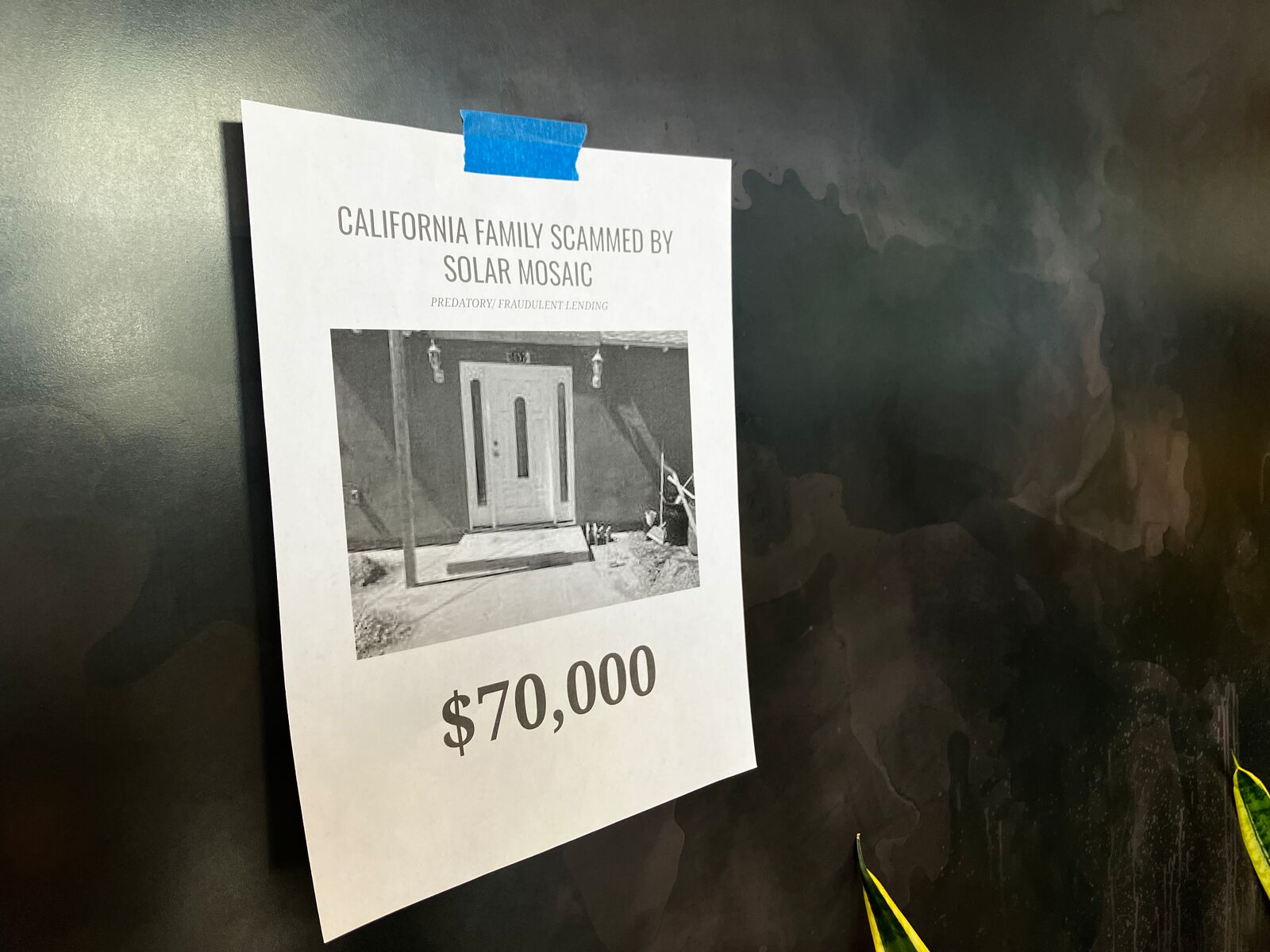

Dozens of Los Angeles residents tumbled out of buses in downtown Oakland on Monday afternoon. Clad in yellow shirts, some wore drums around their necks and others had signs taped to their chests with large dollar amounts—$50,000, $86,000.

They’d driven up from Southern California to protest at the Oakland headquarters of a controversial solar and home-improvement lender. The homeowners and their family members, over 100 people total, are accusing the lender, Solar Mosaic, of teaming up with contractors to take advantage of them.

Solar Mosaic provides loans nationally for solar panels and other home-improvement projects like window replacements or ADU construction. It contracts with construction companies, allowing the companies and their salespeople to help obtain Mosaic loans for their clients.

“You can sell and close a deal in the field, from your truck, or at a homeowner’s kitchen table,” Mosaic tells contractors in a video about its lending app. “A homeowner can sign their loan agreement in a few minutes, digitally.”

The protesters allege that Mosaic is issuing payments directly to these companies for work left partially completed or never even started. The homeowners end up in debt with their home in shambles. They’ve organized with the Los Angeles “Home Defenders” chapter of ACCE, a statewide housing advocacy group that’s active in Oakland as well.

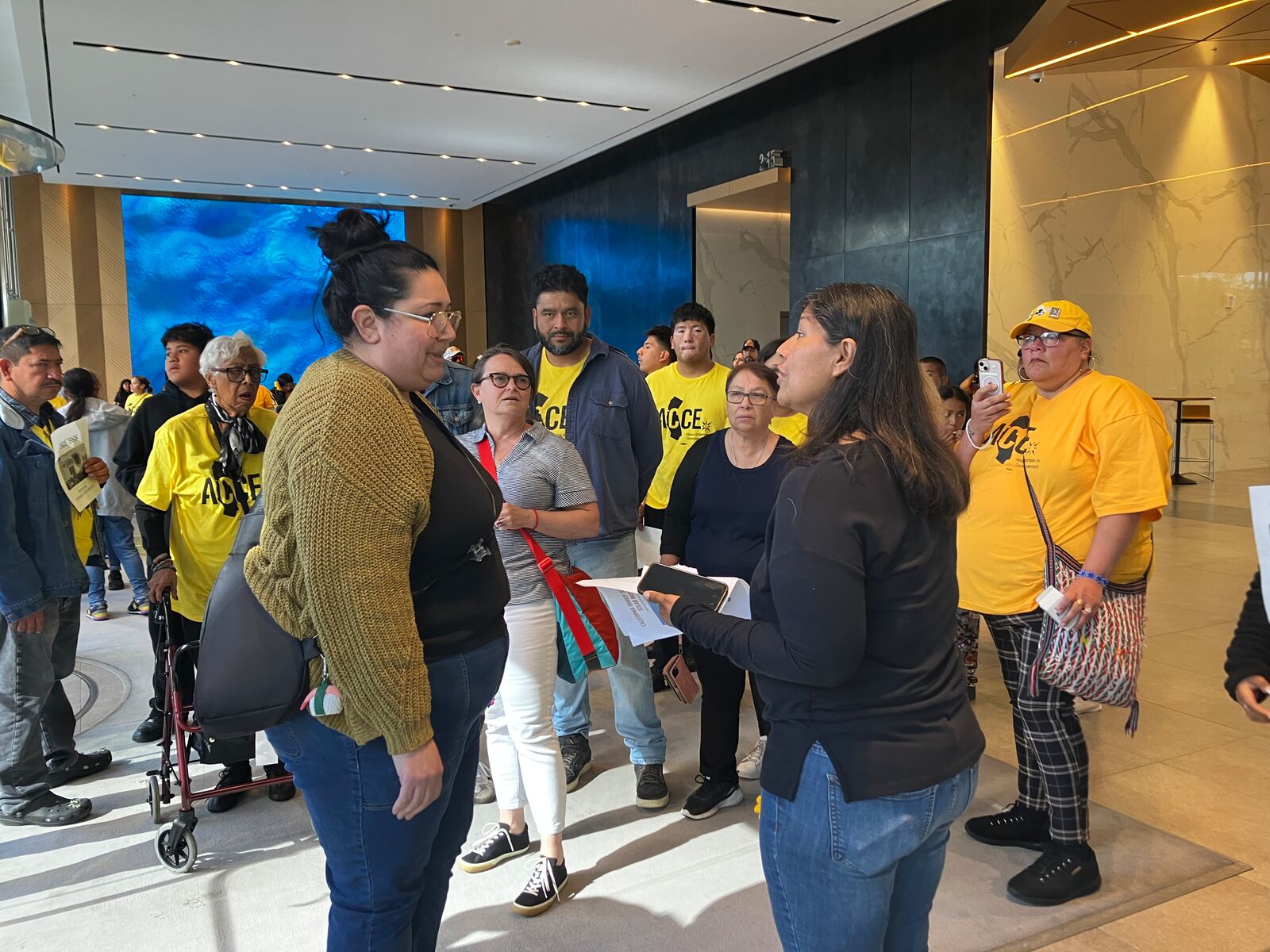

Marching inside 601 12th St., a new downtown highrise, the protesters formed a long line inside the lobby. Solar Mosaic has an office inside the building, though its executives appear to be based in Glendale.

The protesters snaked around the room. They chanted, yelled, shook noisemakers, and banged drums. Security guards and front desk staff glanced at each other and got on the phone. They blocked off entry to the rest of the building, but ultimately allowed the protest to continue for over an hour.

“The bank wants to take our house, the house I grew up in,” yelled a young woman into a microphone. “That’s not fair, right?”

“No!” shouted the crowd.

“I had to drop out of college…and grow up fast to help my mom figure this out, because of corporations like this,” she said.

The group hadn’t come empty-handed. They had written up a letter demanding Solar Mosaic meet with them, cancel their loans, and return what customers had already paid. They wanted facetime with the CEO.

Building an ADU could cost a family their house

Geraldin Alvara hired Viridi Construction in 2021 to convert a garage into an ADU at her family home in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles.

The company, which she found through social media ads, told her the project would cost $150,000. They told her she’d been approved for loans by Mosaic the same day. Alvara told The Oaklandside that the terms of the loan were clear: Mosaic would release payment directly to Viridi once Alvara confirmed work was completed.

But “they didn’t do any work for six months,” she said. Countless calls, emails, and complaints later, Viridi showed up at her door, asking her to sign a new contract with different terms. She refused.

“Come to find out a year later that Solar Mosaic had already released three payments to Viridi”—totaling $54,000, she said. Now she was in debt to the lender. The family—Alvara, her parents, and her three younger sisters—didn’t have the money to cover it. The whole idea was to rent out the new ADU and pay off the loan with the income. But the project was not done and Viridi was nowhere to be found.

“I was going nuts, losing it,” said Alvara. Now debt collectors are hassling the family weekly, posting embarrassing letters on their house. Alvara is getting rejected from credit cards.

“My fear is we’re going to end up homeless,” she said. “This house is our livelihood.”

Lawsuits and legislation

Although The Oaklandside hasn’t independently confirmed Alvara’s story, it closely mirrors other cases described in an accusation filed April 23 by California Attorney General Rob Bonta against Viridi with the state Department of Consumer Affairs.

According to the attorney general, Viridi abandoned or failed to complete numerous projects, used unlicensed salespeople, and overcharged customers. Solar Mosaic was the lender in several cases.

Minnesota and nine other states have also sued or issued warnings to Solar Mosaic along with several other solar lenders.

In response to an interview request, Solar Mosaic sent a statement saying the company “takes homeowner safeguards seriously.”

“In the event a homeowner complains, we work with the homeowner to understand their concerns and seek to resolve such concerns,” said Hal Bienstock, a spokesperson for Solar Mosaic.

On April 22, the day before Bonta filed the accusation with the Department of Consumer Affairs, Solar Mosaic sued Viridi for breach of contract.

“Mosaic disbursed significant loan funds to Viridi Construction, yet Viridi Construction failed to complete the work it agreed to perform on all projects,” Mosaic alleges. The company wants Viridi to refund the money it received from Mosaic for loans that were either canceled or improperly received—to the tune of $6.6 million.

Solar Mosaic also claims Viridi never told the lender that its license was canceled. Viridi Construction’s license was canceled in early 2023 at its own request, according to state records.

Reached at the company telephone number, an employee of Viridi confirmed that the company is not currently licensed, but he said Viridi is still completing work on projects that were already in progress. He said he would pass an interview request on to his boss.

A spokesperson for the California Department of Consumer Affairs licensing board for contractors told The Oaklandside that contractors are required to “cease all work immediately” when their license is canceled, including in-progress projects. She confirmed Viridi is not currently able to contract.

Customers of Viridi have filed 39 complaints on its Better Business Bureau webpage in the last three years. Customers of Solar Mosaic have filed nearly 500.

A bill proposed by East Bay State Assemblymember Tim Grayson, a former contractor, is trying to better protect homeowners from shady lenders and construction companies. AB 2993 would require lenders to directly explain the loan terms to customers, and would prohibit them from releasing funds to contractors until the homeowner has confirmed verbally that conditions have been met. A speaker at Monday’s event said she experienced one of several documented cases of forged signatures by contractors.

“We’ve had clients who are elderly who don’t even have email, and they’ll create a fake email for them,” said Joe Jamarillo, senior attorney with Housing and Economic Rights Advocates. The Oakland-based organization is sponsoring AB 2993.

The bill “puts the burden on the lender to confirm work is complete,” said Jamarillo. If the lender disburses money without confirming the project is done, “it basically incentivizes unscrupulous contractors to stop work when they get paid.” He noted that plenty of contractors are honest and don’t collect payment for work not finished.

Meanwhile, Aida Urizar, who came to Monday’s protest, said she’s appointed herself as an advocate for people like Alvara. By calling companies and filing police reports, she said she’s been able to get close to $1 million in Mosaic loans canceled.

But dozens of households are still in debt with nothing to show for it, she said, “and there are victims here in Oakland too.”

Solar Mosaic responds

A homeowner was telling her story into a microphone in the 12th Street lobby Monday afternoon when Urizar’s phone rang. It was an executive assistant for Mosaic. Urgent “shh!”s broke out around the room and the crowd of 100 fell silent.

Urizar put her phone on speaker. The Mosaic assistant said she’d come by to pick up the demand letter, but wanted assurance that she wouldn’t be bombarded by protestors.

“Your message has been heard,” she said, but “I’m just one person.”

“I promise your safety is not going to be at risk,” Urizar responded. But the group wants answers, she said.

“This is going to go to the right people,” the assistant assured her.

About 20 minutes later, the assistant arrived at the building and met privately with Urizar and a couple homeowners.

Eventually Urizar emerged from the conversation and made an announcement. The assistant had accepted their letter and agreed to set up a meeting with a Mosaic executive the next week, Urizar said. They’d look into the group’s complaints.

“She promised me she’s going to relay this to the CEO,” Urizar said. Relief was palpable in the room. One man teared up. Urizar told them not to get too excited.

She warned them: “This is not going to guarantee they’ll cancel our loans.”